|

A five day detour to the Zongdjian horse racing festival gave our bodies some time to recover and one last glimpse of the rich Tibetan cultural heritage before entering a new cultural realm of Lisu, Bai and Han farmers. As expected the Mekong rose several feet in our absence and was less than 2 meters below the high water mark when we set off from the Lincang bridge. As the water volume increased so too did the level of chaos encountered class IV - V runs were followed by class IV - V boils, whirlpools and surges. It was an awesome section of whitewater and we thoroughly enjoyed it.

For a change we actually had a fair idea of what we were in for over the next 160km due to some detailed accounts from previous expeditions posted on the informative Shangri-La river expeditions web site. There were long and detailed descriptions of one particular rapid called dragons teeth. It was located in a sheer sided canyon and was supposedly extremely difficult to portage. Previous boaters had graded it as almost off the scale and at lower water levels it had flipped most of the rafts that dared to run it. With approximately 3 times more water currently in the river we wondered whether dragons teeth would turn into a suicide run.

Late on the first day we noted a large avalanche scar on river right where the northern face of a hill

had slid into the river. Peculiarly there was no debris at the base of the scar. The debris had been

flushed down stream by flood waters for more than two kilometers, plugging up the entrance to a canyon. It was dragon's teeth. From 200 meters upstream we could see the horizon line drop away significantly and mist rise up from the violence. We eddied out on river right just above the drop to inspect the rapid and to our relief it looked runnable but with the light fading fast it was best left until the next day. Camp was set in the scenic gorge and we settled in for a night under the stars.

had slid into the river. Peculiarly there was no debris at the base of the scar. The debris had been

flushed down stream by flood waters for more than two kilometers, plugging up the entrance to a canyon. It was dragon's teeth. From 200 meters upstream we could see the horizon line drop away significantly and mist rise up from the violence. We eddied out on river right just above the drop to inspect the rapid and to our relief it looked runnable but with the light fading fast it was best left until the next day. Camp was set in the scenic gorge and we settled in for a night under the stars.

The white water was huge over the next two days but loads of fun. Occasionally we would be lashed by gales that always seemed to blow upstream. At one point we were forced to stop above a long rapid because the winds whipped up so much mist off the surface of the waves and holes that we could no longer visually make out the features to avoid. Suddenly the river stopped dead.

We had arrived at the controversial Manwan Dam. The Chinese are in the process of planning and constructing a cascade of 9 dams across the Mekong mainstream in Yunnan, two of which have been completed and another 4 are currently under construction. The dams on the Mekong combined constitute one of the largest engineering feats ever undertaken. To give an impression of the scale, the Xiowan dam due to be completed in 5 years is about the same size as the Hoover dam in the United States and will back up the water for 170km through the gorges, forests and villages we had just paddled.

The pros and cons of large scale hydropower dams can be debated indefinitely with advocates citing a long list of benefits while opponents cite an arguably longer list of negative environmental and social impacts. In most cases where inequities are obvious and clearly defined dam advocates will attempt to mitigate the situation by offering benefits to the peoples and environments most at risk. Although mitigation attempts associated with the highly publicized 3 dams project on the Yangtze were widely considered by the international community to be inadequate the Chinese authorities did in fact devote hundreds of millions of dollars to relocating the most affected people to purpose built cities.

The most striking contrast between the Three Gorges Dam project and the Mekong Cascade Dam Project is that the majority of negative impacts from the Mekong Dams will not be felt by the Chinese population but instead will be shouldered by the rural people of downstream nations including some of the most impoverished on earth. Far from offering to build entire cities to assist the worst affected, as yet there has not been any formal attempts at mitigation with the downstream nations. Interestingly, an environmental impact assessment of the dams on downstream nations was not undertaken by the Chinese until after the Manwan was completed in 1993. The controversy continues, as does construction.

On a personal level I was deeply saddened to see such a great and powerful river subdued into a flat and

lifeless lake. Over the proceeding months I had the great privilege to become the first person to experience the entire upper section of the Mekong from ground level. I had studied its temperament from its playful folly across the Tibetan Plateau to the violent mood swings that erupted periodically when obstructions attempted to divert the flow. I had gaped in awe at kilometer after kilometer of gigantic gorges and attempted to calculate approximately how many billions of tons the river had eroded away along a single 100 kilometer stretch. My calculator did not contain enough digits!

Until now the river had twice shocked me with lessons in my own mortality and instilled me with a million moments of wonder. Constantly alive and relentlessly transforming the world through which I traveled the Mekong to my mind is in fact a living, evolving entity.

In front of us lay a motionless body of water, devoid of character and strength. It was fed by the Mekong yet it contained none of the traits that I had come to know and deeply respect throughout the journey. On the web news we encountered just before starting this section we read that down stream nations were experiencing some of the lowest Mekong water levels on record, negatively affecting millions of local

farmers and fishermen. Yet where we were, just a few hundred kilometers north of Thailand, Laos and Myanmar the river was nearly full. The unfortunate fact was that the majority of the water was being withheld in China to fill the two operational hydropower dams.

I discussed it with Brian and we decided that as a sign of protest against the construction of dams across the Mekong mainstream that will in turn enforce un measured and uncompensated hardships on local peoples in downstream nations, we would not paddle across the man made Mekong Lakes of Yunnan.

At the base of Manwan dam the river sprang back to life. The dam had just started to overflow so the

water levels below this particular dam were the same as above. The white water was awesome. Four meter

plus wave trains were followed by enormous whirlpools and boils that would surely render a kayaker

unconscious should he bail from his kayak. After 6 more hrs of paddling the river again started to back up as we approached the Xiowan Dam. It was the biggest man made monstrosity I have ever seen. Both sides of a huge canyon were thoroughly cemented up to a height of 500 meters. Hundreds, if not thousands of construction workers toiled throughout the site. BANG!! A powerful blast of dynamite scared the hell out of both of us as a section of the gorge wall was blasted into the river.

water levels below this particular dam were the same as above. The white water was awesome. Four meter

plus wave trains were followed by enormous whirlpools and boils that would surely render a kayaker

unconscious should he bail from his kayak. After 6 more hrs of paddling the river again started to back up as we approached the Xiowan Dam. It was the biggest man made monstrosity I have ever seen. Both sides of a huge canyon were thoroughly cemented up to a height of 500 meters. Hundreds, if not thousands of construction workers toiled throughout the site. BANG!! A powerful blast of dynamite scared the hell out of both of us as a section of the gorge wall was blasted into the river.

About 300 meters up the gorge wall on river left a large excavator nudged boulders the size of 40 foot shipping containers into the river. They tumbled, half rolling, half airborne down the near vertical cliff crashing into the river below sending water high into the air. It was an awesome sight. Dozens of workers downed their tools to watch a couple of crazy kayakers sneak along the river right bank above a long class VI rapid caused by the thousands of tuns of rock that had been blasted and dumped into the flow.

We rapidly made our way through the site concerned that falling rocks or dynamite blasts may put a swift end to the expedition. The sheer scale of the construction site was something that will remain etched in my mind for years to come. We had been warned about photography in the site and could not get our cameras out.

The next day we arrived at the second operational dam in China called the Dashaoshan. We were greeted with a surprise in that US$600.00 had been stolen from my bag while we paddled the previous leg. Brian was forced to make a long and frustrating drive to to retrieve more funds from the bank and ultimately did not manage to return to the river for the final stretch in China leaving me to do the last 140km of previously unboated white water solo.

After a nights rest in Dashaoshan village we drove to the put in at the base of the dam to find that only a fraction of the water entering the lake was being released down stream. The Mekong became a new, medium to large volume river instead of extra large volumes we had previously paddled. We estimated that water flows below the dame were about 75% less than could be found above. I spent the next 2 days paddling various sets of previously unboated rapids including two challenging class V's. After 140km the waters relaxed and for the first time I came across commercial cargo boats just north of Simao. I took the opportunity to surf their stern and bow waves but the captains were not as fond of the experience as I was.

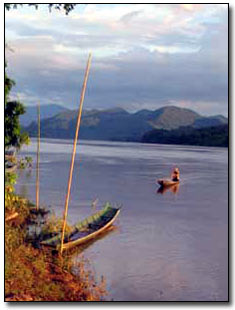

I also started to notice the locals interacting with the river rather than avoiding it. In most of the Tibet and China sections the Mekong is seen as a dangerous obstacle that should be avoided. Yet now, children swam and played while their fathers fished and women came down to the rivers edge to wash clothes. I had crossed into the Dai area of Southern Yunnan. The Dai are the ancestors of modern day Thais and Laos and are as at home in a hardwood pirogue on the river as they are on dry land.

Finally after nearly 3 months in China I was about to enter the South East Asian lands of Thailand, Myanmar and Laos and a new, exciting leg of the journey.

Thank you all so much for your support of the project and stay online for more updates soon.

Best Regards,

Mick O'Shea.

Read About The Complete Mekong Descent

|