|

I was idling the SUV's engine keeping a snail's pace along Merritt Island National

Wildlife Refuge(NWR) loop road. It was early in the morning as I made my way around

the circuit for the first time that day scouting for photographic opportunities. To

my right I spotted an Anhinga wading a small pool along the side of the road.

Anhingas are not uncommon at Merritt but this one was struggling to down a foot-long

snake it had captured! What a photographic opportunity had presented itself. I

quickly pulled to the side of the road and shut down the engine. So far so good: the

Anhinga was still struggling with its breakfast. I opened the rear of the vehicle to

get my camera and capture the prize photo of the trip. Quickly the tripod was

deployed. The Anhinga was now nervously pacing back and forth. As I removed the lens

from my backpack I realized I was in a race to be ready. I needed to mount the lens

hood and the camera to the lens. Fumbling with the mounting hardware wasted precious

more seconds and as I completed the tasks I looked up to see the Anhinga just

'licking his bill'. What I hoped would be the photograph of the trip ended in an

Anhinga 'gulp' as I stood with assembled lens and camera in my hands, the tripod

still three feet away.

the circuit for the first time that day scouting for photographic opportunities. To

my right I spotted an Anhinga wading a small pool along the side of the road.

Anhingas are not uncommon at Merritt but this one was struggling to down a foot-long

snake it had captured! What a photographic opportunity had presented itself. I

quickly pulled to the side of the road and shut down the engine. So far so good: the

Anhinga was still struggling with its breakfast. I opened the rear of the vehicle to

get my camera and capture the prize photo of the trip. Quickly the tripod was

deployed. The Anhinga was now nervously pacing back and forth. As I removed the lens

from my backpack I realized I was in a race to be ready. I needed to mount the lens

hood and the camera to the lens. Fumbling with the mounting hardware wasted precious

more seconds and as I completed the tasks I looked up to see the Anhinga just

'licking his bill'. What I hoped would be the photograph of the trip ended in an

Anhinga 'gulp' as I stood with assembled lens and camera in my hands, the tripod

still three feet away.

During the rest of the day, I had the opportunity to reflect over the latest 'one

that got away'. It occurred to me that golfer's, fisherman and photographers share

something in common, they all can vividly recall the missed putt, the big bass that

shook the hook or the Anhinga that finished its snack before the camera could be

brought to bear. Although they can't remember what they had for breakfast that day,

they will recall these missed opportunities years later.

I won't bore you with the details of other missed photographic opportunities but

others that come to mind are:

1) The McNeil River brown bear that did belly flops to shock fish into submission.

1) The McNeil River brown bear that did belly flops to shock fish into submission.

2) The humming bird that left it's feed so quickly that I had only a good photograph

of a flower.

3) The thunderstorm at the north rim of the grand canyon that left my electronic

cameras incapacitated in the high humidity.

4) The bald eagle that struggled with a snake on the shores of Kacthemak Bay.

The list goes on and on.

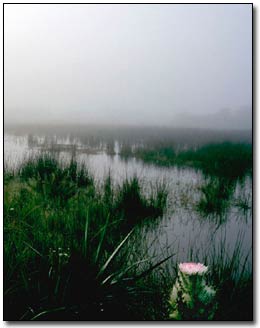

The latest missed opportunity at Merritt Island NWR was followed with a second

chance on the very next day when I happened on a Great Blue Heron with a large snake

in its mouth. Although I have a record of the scene, the image quality is so poor

that it will only serve as a reminder that I don't really need anyway.

chance on the very next day when I happened on a Great Blue Heron with a large snake

in its mouth. Although I have a record of the scene, the image quality is so poor

that it will only serve as a reminder that I don't really need anyway.

Although there will always be 'ones that got away', there are things that a

photographer can do to minimize lost opportunities.

1. Plan. Check your equipment before going on a photo expedition. Thoroughly clean

all equipment. Ensure batteries are fresh and that you have spares. Conservatively

estimate the amount and types of film you will need. Research the area you will be

visiting. Check sunrise and sunset times and optimum locations for each time of day.

For tidal areas, check the tide tables. Of course check expected weather conditions.

Prepare an equipment checklist to be sure you don't forget essentials like filters,

extenders, adapters flash units, instruction manuals, cleaning materials etc.

2. Prepare. Avoid a case of get-there-itus. Being at the scene does one no good if

your equipment is not ready to go, remember my tale of the Anhinga with the snake?

Have your equipment set up and ready to be deployed as quickly as possible. The

night before, refresh yourself on the operating modes of the camera that you will

likely use. Have equipment that you might need staged for easy access. Make sure

you have the correct film loaded for the anticipated initial shooting conditions. My

photograph of the great blue with the snake is unacceptable because I was shooting

early in the morning with an f/4 lens in heavy overcast with ASA50 film!

likely use. Have equipment that you might need staged for easy access. Make sure

you have the correct film loaded for the anticipated initial shooting conditions. My

photograph of the great blue with the snake is unacceptable because I was shooting

early in the morning with an f/4 lens in heavy overcast with ASA50 film!

3. Anticipate. Particularly true in wild life photography, anticipation can often

make the difference between success and failure. Successful sports photographers

need to understand the sport in order to anticipate the moments of peak action.

While they will not always be successful, anticipation increases their odds of

getting an award-winning photograph. In wildlife photography, learning the habits of

your target is important. In all cases, the key to anticipation is observation.

Watching the white pelicans at Sanibel Island's Ding Darling NWR for a short time

enabled me to recognize their behavior before taking flight and to attempt an

in-flight image. Similarly, the nature photographer can increase percentages of

capturing the moment by careful observation and anticipation of the effects of

changing lighting conditions on a scene.

4. Be Patient. Like fishing, photography demands patience. Don't succumb to

chasing the scene or photographic opportunity that lies just around the bend. Too

often you will have spent non-productive time chasing a non-existent opportunity. If

you have planned and prepared properly, stick with your plan for the day unless you

find the situation has changed in favor of another location or plan.

Advice is easy to give but harder to follow. Had I followed my own advice, I may not

have captured the Anhinga and Blue Heron with their prey, but my chances would have

been greatly improved. Just what is the point in beginning the day looking for

wildlife opportunities with your camera body capped and lens in it's case? Had I had

everything assembled and ready to go I might have been able to capture that Anhinga

before he swallowed the snake. The next morning I had a repeat opportunity with the

great blue heron. I had my equipment ready to go but what was I thinking with ASA 50

film early on an overcast morning? I guess I have to conclude I didn't really learn

the lessons from the previous day.

have captured the Anhinga and Blue Heron with their prey, but my chances would have

been greatly improved. Just what is the point in beginning the day looking for

wildlife opportunities with your camera body capped and lens in it's case? Had I had

everything assembled and ready to go I might have been able to capture that Anhinga

before he swallowed the snake. The next morning I had a repeat opportunity with the

great blue heron. I had my equipment ready to go but what was I thinking with ASA 50

film early on an overcast morning? I guess I have to conclude I didn't really learn

the lessons from the previous day.

From now on, I will follow my own advice to plan, prepare, anticipate and be

patient, at least until the next time when get-there-itus overwhelms me.

|