|

Named for 18th century botanist Anders Dahl, Dahlias are native to Mexico and

Central America and were grown primarily for their tubers as a food source, although

their fibers were used in clothing and their hollow stalks for the transportation of water.

their fibers were used in clothing and their hollow stalks for the transportation of water.

The Spanish were the first Europeans to discover 'Tree Dahlias' in the

1500's, but rootstock and seed were not introduced in Spain until the 1700's and at

that time were grown primarily as a food source as the blooms were not particularly

attractive. By the early 1800's nurserymen were creating attractive blooms through

hybridization and for a brief period Dahlias became popular, but interest soon waned

since it was felt they had achieved all possible color and form combinations. In

1872 tubers were shipped from the mountains of central Mexico to Holland, but only

one survived; this one tuber, when hybrid with the earlier stock, became the parent

of the thousands of modern garden Dahlia cultivars.

While Dahlias can be grown almost anywhere, they thrive in wet environments with

cool nights and professional Dahlia growers, hybrid Dahlias for repeatability.

Today, well over 50,000 registered Dahlias exist and that number increases annually,

but many of the blooms that I photograph are unregistered, failed hybrid experiments

that will never be seen again. As a photographer, I prefer the unique form and

movement of the rejected 'blown center' flowers and other anomalies that end up

being yanked from gardens in favor of more consistently uniform blooms.

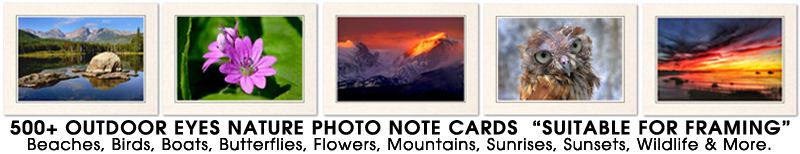

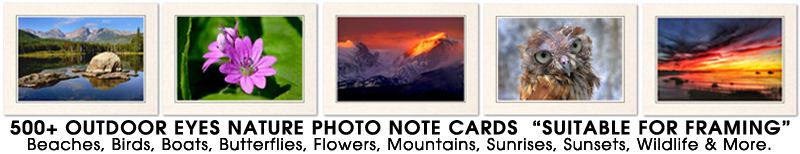

If photographing flowers is a passion for you, as it is for me (and diversity is what you are after), find a grower in

your area and see if he will allow you to photograph his Dahlias. The image

possibilities are endless and of course, the more you're able to shoot and

experiment with any given subject, the better your work will become.

Recommended gear:

1) Macro lens: Preferably one that zooms-growers who grow for shows grow in tight

rows, so the less you move about and disturb their plants the more likely they will

be to allow you to return and it makes composing much easier.

2) Tripod: My camera never leaves the tripod unless I fly somewhere; a tripod will

get you sharper images and slows you down so you can compose more meticulously

(you'll be amazed at how much an infinitesimal movement in your camera can make in

the composition of a close-up photograph).

get you sharper images and slows you down so you can compose more meticulously

(you'll be amazed at how much an infinitesimal movement in your camera can make in

the composition of a close-up photograph).

3) Neutral colored umbrella: Sometimes direct sunlight can make a shot, but as a

rule, overcast skies or even lighting (however you can get it: i.e. the umbrella)

are what you want for flower photography.

4) Backdrop cloth: If you shoot with a background, awareness of or controlling your

background is critical to the success of any image. I experiment more with limited

depth of field, out of focus background and foreground, close-up photography than I

do with anything else in nature-I think it's the most creative venue, although, if

you really want to pop an image a simple black background or any solid color

(experiment) is the way to go.

5) Camera with spot meter: I spot meter everything and expose for the brightest part

of the image-the quickest way to ruin any photograph is to blow out highlights.

Metering is a science and an art and once you have used your spot meter for a while,

it becomes intuitive.

6) Fujichrome Velvia or the Velvia setting on your digital camera: If you want

vibrant color and great contrast, Velvia is all there is; it's the only film I

shoot. High contrast situations (unless you are going for contrast) are not where

the film excels, that's why I do most of my waterfalls and high contrast images in

fog or at least when there is no direct sunlight.

7) Remote shutter release: The slightest movement of the camera will create blur, so

if you don't touch the camera to release the shutter, you'll get much cleaner

images.

8) Lastly PATIENCE: It can be very frustrating to be shooting on a partly cloudy day

and you've metered the light, waited for still air (so there is no movement in the

flower), you're ready to release the shutter and the light changes, so you have to

do it all over again and maybe again and again and again. Stick with it. PATIENCE

has its rewards.

|