|

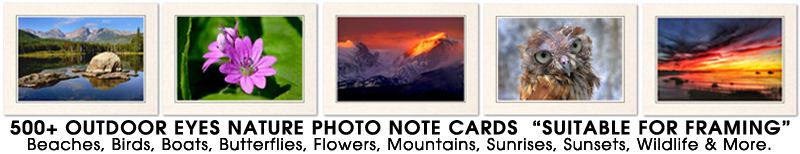

To the Starting Line And The approach:

It is the visions of stunning environments and of regions steeped in ancient culture that will stay with the team longest after our six day four wheel drive ride across China and Tibet to our trek Starting point. In little over 1000 kilometers we past various biomes from regions of temperate pine forest to glacial lakes immense gorges to the rolling grasslands of the Tibetan Plateau. The daily lifestyle of the rural Tibetan people seems to have changed little in centuries with most of the herders living in yak hair tents or mud walled huts. What surprised me most as we traveled day after day along predominantly dirt roads was just how remote and desolate this region is. Besides the occasional nomadic yak herders

camp we would often drive for many hours without seeing a settlement. Considering we were officially driving through China, lack of people is not usually the first thing that comes to mind.

camp we would often drive for many hours without seeing a settlement. Considering we were officially driving through China, lack of people is not usually the first thing that comes to mind.

The drive took us from the Himalayan steps of Yunnan, through the precipitous gorges of Sichuan and finally onto the Tibetan Plateau proper in Southern Qinghai. To the relief of the teams collective backsides we arrived in Zadoi, a bustling little frontier town located where the road stops on most maps of Qinghai on the 15th of April 2004 after 5 long days of driving.

To the Source:

After a day for preparation we finally departed at 9.00 pm on the 16th of April by Beijing 4wd jeep and within one hour of leaving town on white knuckle mountain roads our vehicle had broken down. Our heavily overloaded jeep had popped a hub lock during a gear change and we were forced to limp back into town for repairs.

Two hours of repairs and three hours of treacherous driving brought us to the settlement of Zarching located on a flat plain between snow covered peaks. Doujie invited us inside to enjoy a hot cup of Yak butter tea with some local acquaintances and we took the opportunity to chat with the herders who made their lives from this harsh environment.

We sat around a stove of smoldering yak dung and heard of how wolves had taken some seven sheep the previous night and that bears would periodically come down from the mountains after the winter hibernation to terrorize locals and take livestock. With April being the end of winter I suddenly felt a little less paranoid about bringing a 14 inch machete for the nights alone in the wilderness. After thanking the herders for their time and the copious amounts of slightly rancid yak butter tea we pushed on and just as the sun sank behind distant mountains we arrived at a herders winter settlement on a vast plain covered in snow.

As is the custom we were met by vicious mastiff dogs which fortunately were restrained by chains. Steam and through flew from their mouths as they hurled the full weight of their muscular bodies toward us until when taught, the chain would jolt them back with alarming force. I was glad the chain was thick!! The herders were busy weaving lengths of yak hair into long rolls of course fabric. These rolls are eventually sewn together to form the dark summer tents that play such an important roll in their semi nomadic existence. Without a second thought they offered us a bed for the night and proceeded to fire up the yak dung stove in an empty hut to keep us warm.

We rose early and 8 hours our rattling Beijing jeep persevered through creeks, snow storms and rugged terrain above 4200 meters. The countryside was crawling with marmots and their furry little behinds could be seen darting into burrows constantly throughout the drive. Eagles carved circles overhead while

pinpointing the more careless of the marmots and could occasionally be seen making a swoop in stealth mode to pick up breakfast or lunch.

pinpointing the more careless of the marmots and could occasionally be seen making a swoop in stealth mode to pick up breakfast or lunch.

Eventually by 3.00 pm we had arrived at the furthest point the road would take us, Huze homestead. As we walked in we were welcomed with yak butter tea and raw yak flesh to chew on, the Tibetan equivalent to coffee and donuts. At the entrance of the dimly lit mud walled hut I noticed the carcass of a young yak sprawled across the landing. When I enquired I was informed that wild dogs had made a mess of the poor beast the previous night. My machete was now clearly etched into my mind as an essential piece of camping equipment in a region with no trees. We spent the afternoon at Huze while word was sent to "Bussrr" an old Kampa herder and horseman who was said to know the Mekong headwaters better than any other man.

By 10.00am Bussr had made his way to Huze with 11 horses and quite possibly the most stubborn yak in the world. Big foot as we called him quite simply was not having anything to do with carting a kayak or anything else for that matter to the source of the Mekong. After 2 hours of struggling to tie gear down on the beast whom would almost do handstands to make our job as difficult as possible we eventually opted for the far more cooperative pack horse.

So we set off at lunchtime on horse toward the source which had been my goal for over two years. After many stops to re-adjust the pack horses we pushed on into the evening and at 8.20pm arrived at a large herders tent perched on a wind swept hill at 4300 meters in elevation. We were all quite travel weary by this stage and I set about cooking dinner of noodles with ham chunks. No sooner had I taken the steaming broth of noodles off the flame did news arrived that a man in the neighboring herders camp had been gored in the face by a yak, it sounded serious.

Risky decisions on the Tibetan grasslands:

Nicolas Suaret, a former emergency officer of the French fire service, Jimmy our translator and I decided to ignore our considerable hunger to go and see if we could help. We grabbed our hefty first aid kit housed in two 10 liter, airtight Tupperware containers and trudged across the high grasslands in freezing conditions for 30 minutes to the next camp. Along the way we gathered that a yak horn had penetrated through the mans left cheek and up towards the brain. The locals estimated a penetration of 15 centimeters!! They estimated he had lost liters of blood and the patient repeatedly fell over when he tried to walk.

As we entered the yak hair tent the smell of blood filled our nostrils and the seriousness of the situation immediately became apparent. The man of 30 years lay on his back with his face caked thick with clotted blood. The wound was 11 hrs old, both eyes were completely blue and swollen shut and fresh blood oozed from the patients mouth. What appeared to be a massive gaping wound in the man's left cheek had a small piece of rag protruding from it. We asked how big the piece of rag was and the answer came, the size of a fist!! We immediately approached him and checked his airway, breathing and pulse. Both his breathing and pulse were weak and with so much blood in and around his mouth we were concerned that his airway might become blocked. Then he was semi coherent.

We immediately set about stabilizing his position, clearing the blood clots away from his mouth and nose before placing him on a saline drip to replace the significant fluids he lost, then paused to assess the situation.

We feared he would not survive evacuation which would take 2 days by twin horse stretcher and a further 2 days by 4wd. If what the locals said was correct the wound extended into the skull so movement would greatly increase the chance of fatal blood clots on the brain. We phoned our expedition medical advisor Doctor Ben Burford of the Australian Embassy Emergency Clinic, Vientiane Laos by Sat phone. He gave us the best advice possible and advised us to proceed cautiously. On many occasions foreigners had ended up incarcerated for participating in the death of locals during medical emergencies. It was a sobering thought in an already grim situation.

We called a meeting of the family and asked if they could evacuate the man, they said no. We then explained that to leave the rag in the patients head would almost certainly be fatal due to a severe infection that would follow. It needed to be removed and thoroughly cleaned but even if we were to do this their husband, father and friend could still die either during or after the procedure. After a short meeting they unanimously agreed that we should attempt to clean the wound. They were convinced he would die otherwise and this was his best shot.

We proceeded under far from ideal conditions in the dusty tent. After 20 minutes of cleaning away the clotted blood and to our great relief, the piece of rag in the mans face was not nearly as big as first declared. The Yak horn did in fact penetrate the bone, breaking the nose in the process but did not significantly enter the skull. After 4 hrs of clean up we decided to use steri strips instead of suturing to seal the wound as it was so wide. By 3.30am after leaving a carefully explained course of antibiotics and clean dressings we were on our way back to our own herders camp and a sense of great relief overcame us. It looked like the man would make it. Five days later my support team returned to the camp and the man, still blind in one eye and bed ridden seemed stronger and was fully conscious. The experience really brought home to the team just how isolated we were out here.

Upwards and onwards:

After 4 hours of deep sleep it was time to refocus on our goal of reaching the source and by 9.00am we were up packing the horses to leave. After the previous nights experience I was more than glad that we did not have to contend with loading big foot the unruly yak who was back at Huse munching his way through a mountain of grass.

We began a long day's ride climbing steadily across frozen creeks, steep sided ridges and open valleys along which jagged Jurrassic rock struts reached for the sky. We were to see no people for the next three days but they were replaced by an abundance of wildlife. Throughout the day we saw two wolves, two herds of Tibetan antelope, a pack of wild horses and a wide array of bird life including an assortment of eagles, vultures, geese and ducks.

Originally we planned to reach the source and camp slightly down stream but progress was slow and as dusk descended upon us we were force to pitch camp about 2 hrs trek from the source in a secluded valley at 5000meters in elevation. As we climbed throughout the day I began to notice the affects of altitude and fatigue on the team. Everyone started to get more lethargic and irritable. Our lips and noses began to blister and peel from the icy wind and sun glare. Even so we were fortunate to have good weather. That night was cold and long.

To the Source:

As we made our way up the final valley Doujie our local guide stopped and pulled out his binoculars to begin gazing across to the distant opposite side of the valley. He claimed to see a bear, but when I looked I only saw a large flock of Tibetan antelope scurrying with incredible speed and agility up the gravelly slope. I was amazed that so much wildlife flourished at this elevation. I personally felt fantastic despite a slight headache and as we made our way up the final valley it was with great anticipation that I awaited the sight of Lasagongma Glacier from which the Mekong trickles. We tied down the horses at around 4900 meters and trekked on foot for 30 minutes. At above 5000 meters it is quite incredible how quickly one gets worn out. Every 20 meters or so on the uphill we were forced to stop while gasping for air before slowly catching breath and proceeding.

Finally we came over a ridge of glacial gravel and rocks and there it was. Lasagongma glacier right in front of us. I was ecstatic. I headed over to the base of the glacier where Doujie and Jimmie were busy prostrating in front of a large dark rock located by the point where a small thread of water trickled from the ice, the Mekong began.

We spent some time at the base of the glacier taking photos, drinking the water and resting but when I finally checked the GPS it became apparent that we were at the first point from which water is released at this time of year but the claimed true geographical source was actually above us by 40 meters high up on the glacier. I asked if anyone wanted to come up to the true geographical source. Everyone was too spent so I proceeded on my own. I could see by the fatigue on the faces on Stan and Nicola that they needed to descend as soon as possible so I moved fast.

The final leg was straight up the side of the snow covered glacier and was hard going. At times I was trudging through knee deep snow gasping for breath. After 15 minutes and 6 checks of my GPS there I was. At the geographically declared source of the Mekong River 5224 meters above sea level.

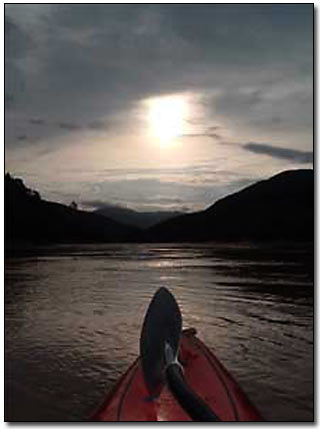

I turned around to scan a breathtaking view of the Mekong valley rimmed by glaciered peaks and rugged limestone and to spent a few moments there by myself. A feeling of joy and anticipation surged through my veins as I looked down the valley that I would explore over the coming months. Two years of work had brought me here and 4800 kilometers of paddling would take me on the journey of a life time down this valley. It was a fascinating thought that the river catchment that started as a trickle at the base of that glacier would expand to become the lifeline for some 60 million people from over 100 different linguistic and cultural groups, that its waters would come to support more aquatic life than the Amazon basin and that its environments would house well over half of the worlds bio diversity.

What a great privilege it will be to travel along this incredible phenomenon from source to sea. With that thought in mind I trudged back down the glacier to where the team were waiting and the descent of the Mekong began. From our planning and observations we estimated that it would be a trek down stream of 140 kilometers before the frozen river would defrost enough to start paddling. The next day the support team broke off and began the trek back to Huze where the car waited. A nomadic herder called Changa and I continued to follow the brittle icy Mekong through a wide valley surrounded by 5000 meter peaks and onto a new series of adventures.

Read About The Complete Mekong Descent

|